There’s more than the usual hush lingering over the hills above Crestone, Colorado, these days, but residents of the area will tell you that only accentuates its power.

Isolated by hours from the nearest big city in the foothills of the ragged Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the San Luis Valley where Crestone sits has, for centuries, been called the “Bloodless Valley” by the local Indigenous nations.

It’s a sacred place, where no battles have taken place, or so the legends say. There are spots within the valley where the silence is so deafening, the stillness of the mountains so assured, that visitors report being overwhelmed by the energy of it all and leaving.

On the home page for Crestone’s town hall is the bold slogan: “The Journey begins at the end of the road …”

If Canadian Hanne Strong had never landed here, perhaps Crestone would be today as it was 40 years ago: a failed mining town populated only by the descendants of its original inhabitants, with no more than the magic of legends punctuating its otherworldly peaks.

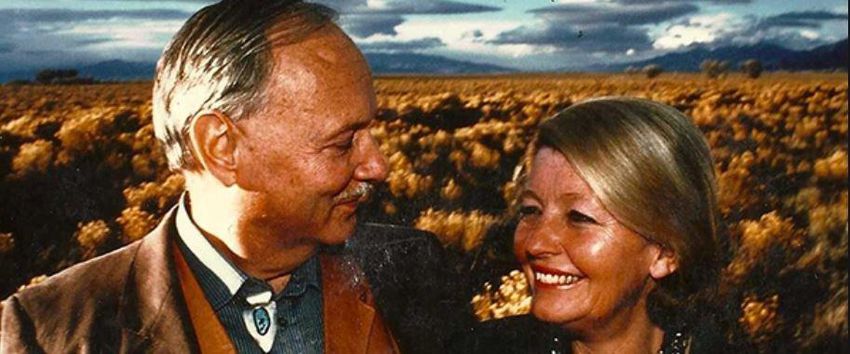

As it is, this is where Hanne Strong and her husband, Maurice, set about creating the most eclectic spiritual gathering place on earth in a bid to bring about what they described as nothing less than the evolution of the human race.

Forty years later, Hanne Strong remains in Crestone, which, empty of its usual visitors because of the coronavirus, is giving her time to reflect on the state of her cause. She’s committed to it still, she says, but also realistic about people and their motivations.

“Around the world, people want their cars, fridges, everything, you know — overconsumption. To just support what’s going on right now, we need 16 Earths,” she says. “This pandemic is just the first warning. Change, or else.

“It’s a warning, from nature.”

The community she helped shape is still drawing in those seeking enlightenment, and willing to do what Hanne describes as the work that comes along with that. But increasingly, it’s also drawing those turning to spirituality as a kind of quick fix for any number of personal and social pains in a chaotic world — including people seduced by dangerous conspiracy-theory-avowing belief systems such as QAnon.

“Right now, having to spend so much time alone, people are in a different space,” she says. “They may be looking a little vigorously (for solutions) because they don’t feel good about things.”

The permanent population of the area around Crestone is only about 1,500, but in a regular year, more than 20,000 people conduct pilgrimages to this area. Throughout the San Luis Valley, an area called the Baca in the hills above Crestone is home to temples, pagodas and centres for more than 30 spiritual traditions from around the world.

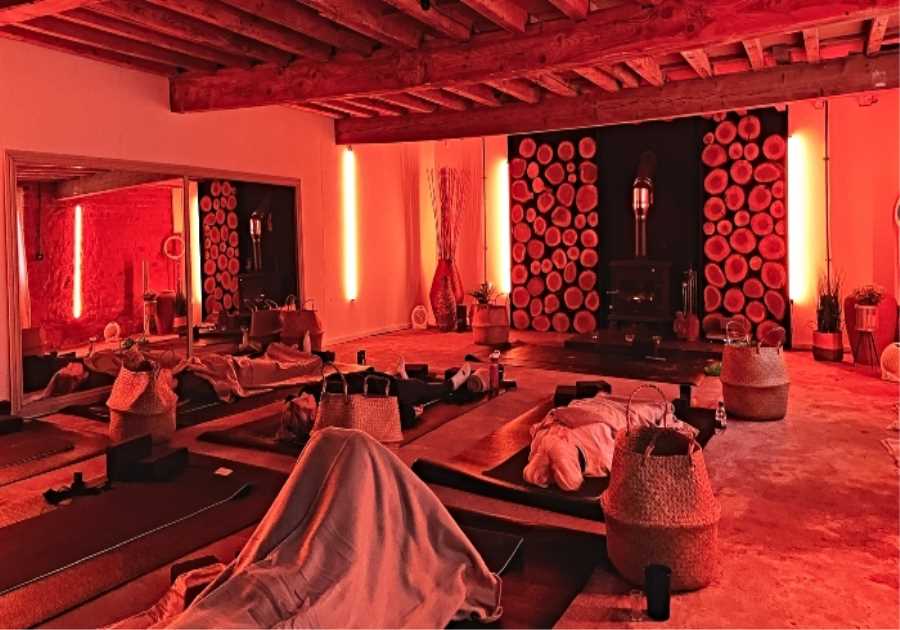

A drive through the winding Camino Baca Grande outside of town reveals a spiral ziggurat in the style of the ancient Mesopotamian shrines, a Tibetan meditation centre with a traditional stupa to represent Buddha’s enlightenment, and a straw-bale sanctuary dedicated to a Japanese philosophy of natural farming and art appreciation.

There’s also a multi-faith outdoor funeral pyre, and dozens of other centres for worship, self-discovery and meditation. If it were all grouped together, rather than distributed across a 200,000-acre ranch, it might look like a theme park for the sacred.

All of it — each structure, centre and temple — is there because of the Strongs. And as the allure of generalized spirituality — with its promise of self-directed enlightenment, compared to traditional religions — grows, Hanne has watched as her harmonious marketplace for spirits has become increasingly contested.

It should be no surprise that the Strongs’ labours changed the area forever, since there is little the couple touched that was not transformed.

Maurice was once dubbed “the most powerful Canadian” by the CBC. He was a tireless businessman, the erstwhile president of Power Corp. Canada and the eventual executive director of the UN Environment Program. The New Yorker once wrote of him: “The survival of civilization in something like its present form might depend significantly on the efforts of a single man.”

It was one of his new business ventures that brought the couple into the United States in 1978, and that’s when Hanne first saw Crestone — the place that they would move their home to, leaving Calgary.

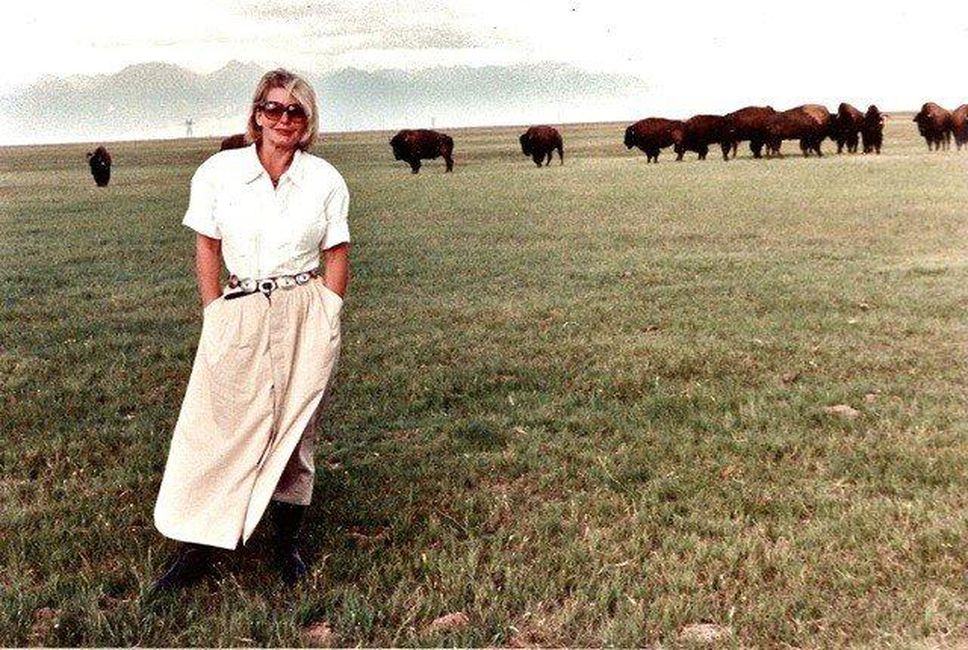

“One day we flew into this ranch, I got off the plane, looked at the mountains and said: Well, this is it,” Hanne told the Star. “This place is going to bring into a new civilization of people — which is evolved beings.”

Hanne says she knows the goal of evolving the human race sounds lofty. But it’s the one thing, she says, she’s always wanted to work toward.

When they arrived in the late 1970s, the Strongs already owned what was then the Baca ranch — a retirement community had once been planned there, then scrapped.

Unlike her husband, whose parallel business and ecological efforts earned him the occasional ire of both groups, Hanne had always been drawn to simple, grassroots forms of environmentalism — the kind that encouraged individuals to appreciate nature and to experience the ways in which they, too, were a part of it.

She became a student and friend of chief Robert Smallboy of the Ermineskin Cree Nation in Alberta, and once used her connections to secure his meeting with pope John Paul II, to advocate for the pontiff’s help in protecting Alberta lands from industrial extraction.

Though she was married to a man who at his death was credited with founding the international environmental movement, it was Smallboy’s activism — the way he led a group of Indigenous people to live in a self-sustaining, traditional way in the wilderness east of Jasper — that Hanne Strong says she understood to be the truest form of environmentalism.

In Crestone, Hanne saw a place of intense natural beauty where she could forge connections with the land in the ways Smallboy and others had taught her. And, as she tells the story, a local mystic soon came to their door with a prophecy: She was meant to turn this place into a gathering place for spiritual traditions of the world.

That, she thought, was how to promote real change in the world: Create a gathering place that — one visitor at a time — would increase the consciousness of people around the world. As a concept it was, as she understood it, rooted in Indigenous traditions she learned about in Canada. Not institutionalized religion. Not governments, and corporations, but spirituality was the key to human evolution, she thought.

“That means that they see reality. They live in a realistic way. They have a connection to nature that is healthy and their view of life and so on is a healthy view: that you do not destroy what gives life,” she says.

Maurice died in 2015. Strong-willed Hanne remains in Crestone, presiding over their unique-in-the-world spiritual marketplace, with all its hope and contradictions.

Once a person who hobnobbed with former prime ministers and, by her telling, rebuffed the late Toronto gold tycoon Peter Munk when he raised an idea to mine the Baca, she is now a Crestone institution unto herself, living on the ranch with her great-grandchildren, venturing into the mountains for the occasional retreat, and into town for groceries from the natural-food store.

Over the course of decades, Hanne did what she could to, as she saw it, evolve the human race. She took the massive property her husband’s industry had purchased and, piece by piece, she gave it away.

Jim McCalpin first approached Hanne and Maurice Strong as a PhD student researching fault lines. It was 1979 and he wanted to study the Sangre de Cristo range, which meant getting permission from the Strongs to survey their land.

“I met the Strongs in the summer of ’79 and Maurice gave me the run of the ranch and he said: ‘Knock yourself out, kid,’” McCalpin recalled. He fell in love with the area that summer, vowing to himself to return to the stunning peaks and utter seclusion for retirement.

Yet it also puzzled him. Crestone was the height of remoteness — three hours from Colorado Springs at the end of a road that had only recently been paved. The few people who worked there kept their cast-iron stoves from the 1800s working so they didn’t have to order new, modern ones.

What were these wealthy Canadians doing there?

“You could tell they were really intelligent sophisticated people and you wondered: What are they doing here in this town in the middle of nowhere?” he says. “I was 29 years old and I already saw: This is strange, I wonder how long they’re going to stay.”

In 2021, McCalpin finds himself sharing Crestone with Hanne Strong. He returned in the early 2000s after the advent of the internet made it possible for him to work remotely.

And they speak about the place with similar reverence.

“You’ve got deer in the yard, bobcats in the road, the elk bugling and the thing that you notice when you come here is it’s quiet. When the sun goes down, it’s pitch black. There’s no light here,” McCalpin says. “It’s like living in nature in the way that 95 per cent of humanity really can’t imagine anymore.”

The connection to nature that Hanne felt in the Crestone area is what has turned it into a spiritual meeting place and, as McCalpin tells it, kept the town alive.

In his role leading the tiny Crestone History Centre, he notes the town was set up during a gold rush but was never particularly rich in ore. The Baca Ranch employed the few people who stuck around through the early 1900s and, heading into the 1970s, the town was nearing abandonment again before the Strongs came along, turning the Baca into the region’s lifeblood once again.

NURTURING COMPASSION, the latest film about the 17th Karmapa produced by Crestone Films, is now available on Amazon. Visit http://a.co/d/2LCHW3p

The couple’s arrival was not without controversy. Maurice was involved in a project aimed at exporting water from the Baca Ranch aquifer, which garnered massive local opposition and never happened.

But the couple’s spiritual project was another story. They set up the Manitou Foundation and started giving away land to spiritual groups from all over the world, the idea being to be discerning, but inclusive: projects had to be serious spiritual ventures with, in Hanne’s view, the ability to introduce people to a more enlightened version of themselves.

“You get help from nature here to quiet down and get in touch not only with yourself but with the cosmos and with nature,” Hanne says. “So there’s certain sacred places around the world that have this high energy that helps people quiet down, tap in and evolve.”

Some in the town proper would prefer to do without the attention brought on by the Baca and all its spiritual endeavours. Crestone’s mayor, reached by the Star, initially agreed to an interview but later said that although she has respect for Hanne, she didn’t want the town to be associated with the Baca.

Loading…

Loading…Loading…Loading…Loading…Loading…

The land grants provided through the Strongs’ Manitou Foundation, along with yearly grants donated by Mary and Laurance Rockefeller, kept dozens of spiritual retreat centres running in Crestone. In a way, it was fringe, with only the most dedicated New Age types venturing there for spiritual advancement.

But in another way, what the Strongs did fit with the times. Linda Woodhead, a U.K.-based scholar of spirituality, has spent the better part of her career studying the rise of “spirituality” as an alternative to religion.

“The line is normally drawn as religion having external authority over the people, and spirituality being self-directed,” she says. “Spirituality fits with a lot of modern understandings of greater equality, and it allows people the freedom to explore things for yourself.

“You get this marketplace where you can shop around.”

The Baca area has become a sort of physical manifestation of that marketplace of spiritual ideas where visitors can hop between spiritual experiences — trying a vision quest with one group on a Monday and an art-guided meditation with another on a Friday.

It drew Matthew Crowley in, gradually. He was just about 40 years old, travelling across the country searching for meaning after leaving a job as a truck salesman that he’d found not just unfulfilling, but eventually demoralizing.

Crestone just happened to be the place he hitched a ride to with a friend one day. And there Crowley discovered the Shumei centre: A centre for a Japanese philosophy centred on natural food production and art as a way of reaching enlightenment.

He stayed 15 years, grounded by meditation, a job at the Shumei and his wife, whom he met there.

“I like to ask people: What is Crestone for?” he says. “My point is that, for most people, it’s a place for people to go, have an experience, learn something and go back out into the world where (that lesson) is more needed.”

After 15 years and countless “profound and miraculous” experiences, Crowley, his wife, and nine-year-old recently returned to Massachusetts, the state from which Crowley originally hails.

“If I learned one thing, it was that I am nature,” he says. “We are not separate from it and so much of what is wrong with the world comes from that disconnection.”

Crowley, who says he became friends with Hanne over the time he spent in Crestone, credits her entirely with making the town what it is today.

The quest for meaning that has become such an ingrained part of Crestone has also left the community vulnerable to the darker forces that have come with spirituality entering the mainstream.

Spirituality began as a fringe movement directed by women and, in its most idealized form, embracing freedom and self-discovery. But as it has become more mainstream — with meditation retreats becoming commonplace and people buying healing crystals on Amazon — so too has spirituality mixed with other human tendencies, such as political allegiances and conspiracy theories.

Hanne herself has noticed as people coming to Crestone seeking spiritual enlightenment have begun to include those she views as misguided or, perhaps, lazily guided, including people who believe in the quasi-spiritual QAnon conspiracy theories, which claim there is a corrupt and pedophilic shadow-state called the “cabal.”

There was also an alleged cult that set up in Crestone, known as Love Has Won, which performed what it called “etheric surgeries,” essentially promising to cleanse people, and prompting believers to leave their families and give their money to a woman they believed to be God.

“You have to look at a very old spiritual law: where there is light there is dark,” Hanne says of these groups. “So there is division in Crestone, no doubt about it. You’ve got right wing, you’ve got left wing, you’ve got people who are highly evolved and not evolved at all.”

“It’s a mix of everything. It’s a microcosm of the world.”

Conspiracy theories have always been present in Crestone, to a degree. Crowley pointed out that some such theories floated around Crestone about Maurice and Hanne Strong themselves — notions that their attempts at setting up educational spiritual institutes were really aimed at world domination.

But as American political divisions deepened in recent years, as spirituality became more mainstream, Hanne noticed something change in her spiritual community.

“People are desperate,” she says. “People are just looking everywhere for answers and some people are going (conspiracy theories) and believing it.”

The online theories, which, like QAnon offer both a villain and a salvation, dangle something akin to a shortcut to spiritual enlightenment. And that’s not the “deep work” Hanne Strong is going for.

Though she set out to change Crestone believing spiritual enlightenment was the key to evolving humankind, and she still believes it today, Hanne is now resolved to a more bleak understanding of the world. Most people, she has concluded, continue to take more from the Earth than they give back. As she watches people purporting to have a spiritual mission go on to get involved in QAnon or other shadowy theories, she sees this as a sign of the same.

“I think definitely it has to do with people that have never done the real deep work,” she says. “They’re gullible, they’re lost, and some of their theories are exciting. With the pandemic, people have had more time to spend on their computers to get into this stuff.”

There are those in Crestone who view its spiritual pull — the fact that thousands of people travel there for spiritual awakening — as evidence that it is a nerve centre for a worldwide consciousness change. And they embrace that even as negative forces come with the good. Thinkers and long-term Crestone residents, such as William Buehler, have claimed that what happens there trickles down to the rest of the world

In an op-ed in the Crestone Eagle, a local newspaper, the leader of the Crestone Spiritual Alliance, a quasi-representative body for 25 spiritual centres in the area, said the pandemic may be a moment of reckoning which spiritual people have been awaiting.

“Should this coronavirus invasion turn out to be the up-ender that shakes up everything to the core, then the Crestone Spiritual Alliance is willing to find itself being redefined by the necessities of our common welfare,” he wrote. “Crestone may well be a place at the centre of the destiny of the future.”

Crowley says he’s always held a more moderate view about Crestone’s impact — that, primarily, its power is in the obvious beauty of the area, and the sense of remoteness visitors get when they go there.

But he doesn’t rule out the idea of supernatural, energetic forces either. He says he just doesn’t know. And he doesn’t think anyone knows for sure.

“Is there an energy to the place, beyond the obvious? Probably,” he says. “But the obvious is reason enough. If you go there and you look up at the Milky Way and you hear that silence, it’s moving in a very human way.”

If Hanne is optimistic, it’s only about the future generation — young kids who might grow up valuing regenerative farming and sustainability, a oneness with the planet. In her own home, she lives with three great-grandchildren who remind her of that.

“That’s the only hope I see,” she says. “That kids will learn to live a very simple, evolved lifestyle.”

Did you miss our previous article...

https://yogameditationdaily.com/meditation-retreats/monk-in-modernity-bhante-sanathavihari