Jamie Wheal was feeling out of place. In Colorado, where he and his wife, Julie, lived for a decade, the towering peaks of the Rocky Mountains had been a reliable source of grandeur, an easy way to help maintain an internal compass. When they moved to Austin, in 2007, he was disoriented—geographically, but also culturally. “Here, there was nothing to orient with,” Wheal told me this spring. “And I was just unmoored.”

Wheal has since found his way. He’s cowritten a popular book about flow states—the calm and focused feeling of being “in the zone”—and says he’s been hired by the likes of Google and the Navy SEALs to advise them on achieving peak performance. The company he started in 2011, the Flow Genome Project, hosts workshops in remote settings that are attended by all manner of industry moguls, including members of the global tech elite. Wheal has become an established, if ambivalent, member of Austin’s “alpha radical scene,” his way of describing the thought leaders, lifestyle entrepreneurs, productivity gurus, tech investors, and wellness influencers who are congregating in the city in ever-growing numbers. He’s friendly with Tim Ferriss, of 4-Hour Workweek fame. When I asked Wheal if he hung out with controversial podcast titan Joe Rogan, he half-demurred: “We just run into each other socially.” Same goes for Elon Musk.

Wheal, who at 49 is tall and lean and classically handsome, suggested we meet at the Hill of Life, the steepest part of Austin’s Barton Creek Greenbelt Trail. There, I quickly learned that Wheal walks fast and speaks faster, stringing ideas about neurobiology, ecstatic experiences, and influencer culture into a hypnotic patter. Wheal’s labyrinthine logic would’ve been tough to track regardless of circumstance, but it proved particularly tricky as I picked my way over slippery rocks while clutching a cup of coffee in one hand and an audio recorder in the other. “I do most of my interviews on stand-up paddleboards,” Wheal called over his shoulder at one point. When we made it down to Barton Creek, the trail’s destination, I was relieved to sit on a limestone outcropping and catch my breath while Wheal’s golden retriever, Aslan, dashed along the waterline.

Wheal has always been an overachiever, but it’s only in the past handful of years that his life has gotten glamorous or, as he puts it, “ridiculously Zelig/Forrest Gump–ish.” Before that, as he tells it, he and Julie had always gotten by simply, working as educators and devoting their spare time to experiences that immersed them fully in the moment: late-night bluegrass jams with friends, epic trips into the mountains. But as the kinds of once-fringe ideas that Wheal touted gained purchase in the 2010s, Wheal’s profile rose too. As he and his coauthor Steven Kotler put it in their 2017 best-seller Stealing Fire, the world is now full of “military officers going on monthlong meditation retreats, Wall Street traders zapping their brains with electrodes, trial lawyers stacking off-prescription pharmaceuticals, famous tech founders visiting transformational festivals, and teams of engineers microdosing with psychedelics.”

Those hordes of microdosing engineers are partly why Wheal can drive a brand-new Mercedes Sprinter van and post selfies with Richard Branson. But they’re also cheapening everything he holds dear. “Everyone has found their way into this lane, and it’s suddenly become incredibly crowded and noisy,” he told me.

In his most recent book, Recapture the Rapture, published earlier this year, Wheal seems to be at times pitching himself as an ambivalent anti-guru, questioning the culture of techno-optimism that brought him success. But is anybody buying?

Wheal with his wife, Julie, in 2018.

Courtesy of Jamie Wheal

Wheal kitesurfing in Baja California in 2018.

Courtesy of Jamie Wheal

Wheal spent the first eight years of his life in England, and evidence of that time is still present in the broad vowels of his not-quite-British accent. His father was a Royal Navy pilot, and his mom was a nurse originally from South Africa. Both parents had high standards for their three children. Wheal spent much of the rest of his youth in Maryland, near the Naval Air Station along the Patuxent River. He channeled his energy into windsurfing in the nearby Chesapeake Bay and reading anything he could get his hands on. His parents wanted him to attend the U.S. Naval Academy; instead, at sixteen, he enrolled at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, focusing on “all things non-Western”: Eastern philosophy and religion, historical anthropology, Indigenous studies. During his sophomore year, he met Julie, then a senior, at a bar and invited her over to his place to watch videos of him windsurfing; they’ve been together ever since. A few years later, Wheal was applying to graduate programs in history when he saw Jeremiah Johnson, a 1972 western starring Robert Redford as a nineteenth-century mountain man. “I was like, ‘F— me, where are those mountains?’ ” Wheal told me. He jettisoned his dream of attending Yale and headed instead to the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Boulder turned out to be a great place for a young seeker with an appetite for adrenaline. It was the early nineties, and while much of the rest of the country was still in a cloud of post-Reagan conformity, the Rocky Mountain region remained a hub for countercultural ideas—and extreme sports. Wheal had an appetite for both. He found common cause among those who microdosed LSD before riding their bikes down mountains. Because these intrepid types spent their days engaged in death-defying hobbies, they were less frivolous than other hippies he’d met. “There was far less deference to New Agey bullshit or people getting snookered by gurus,” he said.

At the university, Wheal earned a master’s degree in American studies and environmental history; between semesters, he and Julie, by then a Montessori teacher, traveled around the West in their 1976 Westfalia van. One day, during the summer solstice, they summited Oregon’s Mount Hood at sunrise before skiing down the upper part of the 11,000-foot mountain, which is covered in snow year-round. Then they biked through a nearby old-growth forest and, later, drove over to the Columbia River for a sunset windsurfing session. “And that was just a completely unscripted day,” Wheal said.

After one “exceptionally mind- and time-bending experience” at a backcountry hot spring in California, Wheal came up with a vision for his PhD dissertation. He believed the entire discipline of history was working from an outdated model of time: Newtonians in a quantum physics world. He would give the field a new, nonlinear way to conceive of time, which he called, rather opaquely, polychronic quantum epistemology. But when he got back to Boulder, he says, it became clear that academia wasn’t interested in that kind of world-shaking upgrade. Unable to put a dissertation committee together, Wheal abandoned his doctorate and left academia.

He and Julie spent the next decade as teachers and administrators at alternative schools throughout the West, where students learned outdoor skills alongside traditional (and not-so-traditional) academics. In 1997, Wheal says, they led a trip to Tibet, and their students became the youngest group of Americans to reach Camp 3, on the north face of Mount Everest. At the High Mountain Institute, in Leadville, Colorado, Wheal says, he took students into the Rockies, where they studied avalanche physics by day and slept in snow caves by night.

Wheal was still in his twenties, teaching at a boarding school in California, when the headmaster gave him a book, A Brief History of Everything, that captured his imagination. The author, Ken Wilber, shared Wheal’s omnivorous appetite for knowledge. Wilber, a Colorado-based guru, was attempting to synthesize all forms of human thought into a singular framework that he called Integral Theory. In books like A Brief History of Everything and A Theory of Everything, Wilber explained, well, everything, displaying a fondness for sorting the world’s clutter into categories and plotting it on graphs and quadrants. Wheal was drawn to Wilber’s promise of a clean, rational mysticism, one that drew on scientific sources as well as esoteric ones. “It was such a lifesaver for me at the time,” Wheal has said.

Despite its cultishly obscure aspects, Integral Theory gained a wide following in the nineties. Alternative-medicine advocate Deepak Chopra was a fan, as were musicians Alanis Morissette and Billy Corgan, who fronts the Smashing Pumpkins. Al Gore told the New Yorker in 1998 that Wilber’s The Marriage of Sense and Soul: Integrating Science and Religion was one of his favorite new books; his friend Bill Clinton was also a Wilber enthusiast. Whole Foods cofounder and Austinite John Mackey was an Integral insider and incorporated Wilber’s philosophy into his Conscious Capitalism movement.

In the early 2000s, Wheal and Julie founded a small Montessori school in a hilly town in central Maryland that incorporated Integral ideas. In 2005 Wheal taught a class at Esalen, the famed hippie enclave in Big Sur. The course, “Integral Learning and Leadership for Young Adults,” combined tai chi, organic breakfasts, service work, journaling, and excursions in nature.

Two years later, he got a call from the Stagen Leadership Academy, a Dallas-based management consulting firm founded on Integral principles. “We work with power,” CEO Rand Stagen has said, meaning politicians, heads of corporations, and megachurch pastors. The company set up shop in Dallas because, according to Stagen, “that’s where the need is, that’s where the work is.” Wheal’s growing reputation within the Integral community had brought him to Stagen’s attention, and Wheal agreed to take a job as a senior consultant at the firm. Instead of teaching young people, he’d be focusing his work on business executives. “Drawn to the work but not drawn to Dallas,” Wheal says, he and Julie bought a house on Lake Austin, where they settled, somewhat uneasily, into their new lives as Texans.

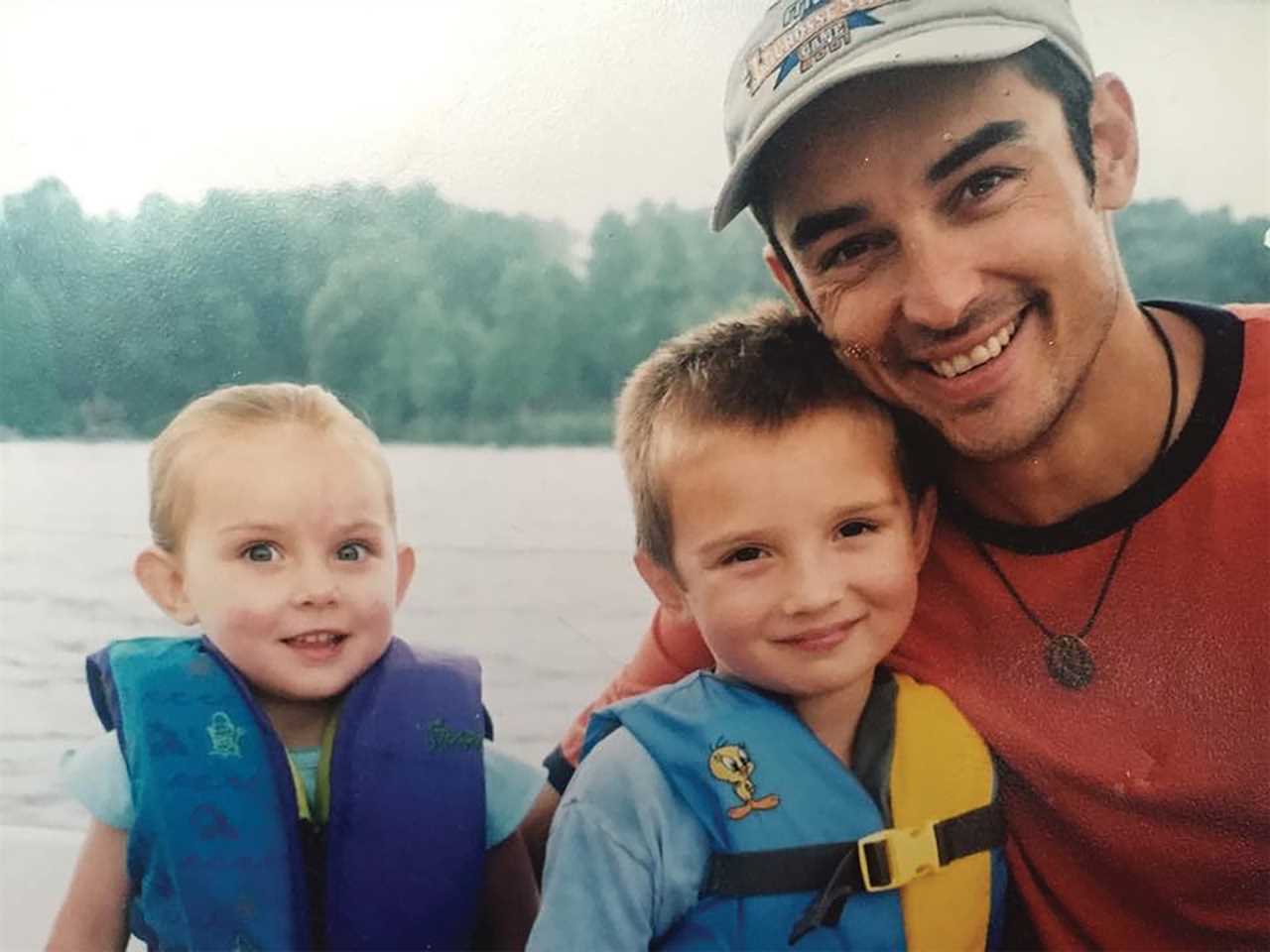

Wheal sailing with his children in 2005.Courtesy of Jamie Wheal

In the years after Wheal moved to Austin, a new scene was coalescing in the city, one built by disparate-seeming groups: the tech bros schmoozing at SXSW Interactive; the VC funders; the clean eaters converging at the Paleo F(x) conference; the down-dogging yogis; the don’t-tell-me-what-to-do libertarians; even, on occasion, the Alex Jones conspiracists. Despite their surface differences, they all tended to take an entrepreneurial, experimental, individualistic approach to life. They were suspicious of institutions but devoted to the hustle, vaguely countercultural but highly ambitious. Wheal’s angle on the world—his interest in both rational mysticism and improved performance metrics—appeared to align with this loose cohort.

Wheal and Julie, now the parents of two children, found what adventure they could in suburban Austin. They took up wakesurfing and hydrofoiling. The alpha antislacker in Wheal was thrilled to find that Austin was home to a vibrant community of former Olympians and other elite athletes; both kids eventually became high-level competitive swimmers. At Stagen, Wheal advised business owners, drawing life lessons from his years as a wilderness guide and outdoor adventurer.

But while the work was lucrative, he grew restless. Wheal had always put freedom at the center of his life; now here he was in a corporate job with mounting domestic responsibilities. “I would get trotted out as the, like, mountaineer leadership guy who’s gonna tell you cool, sexy things,” he said. “But if I’m not continuing to climb, I’m just pimping out a former life.”

After a few years, Stagen asked him to be a partner in the firm. It felt, Wheal said, like a marriage proposal—a serious commitment requiring him to be all in. He was in his late thirties, and he had a bleak vision of himself at fifty, schmoozing at the Austin Country Club. He decided he couldn’t do it. “I was raised in a hypertraditional British family where nothing less than perfect was ever allowed. And I realized that because I was trained to be perfect, I could never be great, because greatness requires spectacular failure. And it took me that long to get the courage or to be out of other options. But fundamentally, I was like, ‘I have to at least take a swing at great.’ ”

He considered blowing up his life in other ways too. In 2011, just a few months shy of his fortieth birthday, he attended Burning Man, the infamous counterculture festival in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, for the first time. On the way, he had a fraught phone conversation with Julie about the future of their marriage. In the middle of the call, his car descended the Sierra Nevada mountains, and reception cut out. For a brief period, the state of their relationship was uncertain. But one morning during the festival, as he watched the sun rise over the desert, Wheal had an epiphany: he could find greater depth, and greater freedom, in committing to his marriage rather than fleeing from it. He describes this as the moment when he stopped being a boy-man and became a man-man.

“I realized that because I was trained to be perfect, I could never be great, because greatness requires spectacular failure.”

Meanwhile, his career was taking an unexpected and promising turn. Wheal’s interest in adventure sports and self-experimentation, as well as his experience importing lessons from those realms into the business world, made him an ideal partner for the journalist Steven Kotler, who made his career writing fast-paced, science-inflected self-help books with titles like The Art of Impossible: A Peak Performance Primer and Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth, and Impact the World. The two men began establishing themselves as experts on flow, the state of being absorbed in a project or activity to the point of losing track of time. The idea was popularized by the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who wrote the seminal book on the topic in 1990. Athletes in the zone, painters immersed in their work, and even children building a complicated block tower can experience flow.

Neither Wheal nor Kotler had degrees in neurobiology or psychology, but that didn’t matter much. The 2010s were becoming the heyday of the thought leader, a figure who was something like the influencer’s intellectual cousin. He (and he was usually, if not always, a he) made money by selling his wisdom and expertise to the general public (via books, podcasts, and TED Talks), fans (via courses and retreats), and corporations (via speaking gigs and consultations). The thought leader was not typically an academic but rather someone who translated academic concepts into bite-size, actionable commentaries and combined expansive ideas in unexpected ways. Wheal, with his magpie interests and remarkable ability to pluck from his brain an appropriate quotation for whatever subject was at hand, was unusually well suited to the role.

Wheal and Kotler launched the Flow Genome Project, an organization for studying altered states and peak performance, among other things. They gave lectures, wrote articles, and made themselves available for interviews. Wheal contributed to Kotler’s 2014 best-seller The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance. But Wheal also says he thought the idea of flow was reductive and preferred to talk about extasis, the Latin word for transcendent, self-forgetting experiences. In 2017 he and Kotler explored that subject in Stealing Fire: How Silicon Valley, the Navy SEALs, and Maverick Scientists Are Revolutionizing the Way We Live and Work.

Stealing Fire, which was named one of the best business books of the year by CNBC, read like the literary equivalent of a TED Talk, with insights delivered in discrete, optimistic chunks. But it was also edgier than your typical business book. Before the author Michael Pollan introduced NPR dads to microdosing, Kotler and Wheal extolled the benefits of psychedelic experimentation for high-powered professionals, touting, with improbable precision, “a 200 percent boost in creativity, a 490 percent boost in learning, a 500 percent boost in productivity.” The book included a section on Burning Man, describing its attendees as “a tech-nomadic glitterati” including “senior vice presidents from Goldman Sachs, heads of the largest creative ad agencies in the world, and leaders of the World Economic Forum”—and, of course, Elon.

The book also advised readers on legal ways to bring more flow into their lives, via music, meditation, extreme sports, and sex. Stealing Fire raised Wheal’s profile among the booming wellness-obsessed personal-development crowd. “I was very drawn to the elegance of his language,” Camila Fernandez, a Miami-based research psychologist, told me. “The fact that it wasn’t academic like I was often dealing with at work but also wasn’t fluffy New Agey—it bridged the two things, cultivating spirituality and also the intellect.”

With the success of Stealing Fire, Wheal was firmly established as a thought leader. His audience was eager to buy access to his presence and insights. He hosted week-long retreats featuring acro-yoga (a combination of yoga and acrobatics) classes and breathwork sessions that were covered by the New York Times, and he launched a one-on-one coaching program “designed only for high-performing leaders who are making a positive impact in the world.” Back at Esalen, he preached a kind of rational, muscular form of self-exploration, telling his students they’d be engaging in the psychological equivalent of BASE jumping. There was a course to get certified in “Flow Genome coaching,” as well as more affordable online programs. He led groups on week-long backpacking trips in the canyons of Utah, and he brought “flow-enhancing equipment”—including a twenty-foot swing that allowed users to spin around in a full 360-degree loop—to Google headquarters, in Mountain View, California.

The efficacy of all this is up for debate. Emily Willingham, a former research scientist and author of The Tailored Brain, told me that the Flow Genome Project struck her as dubious. “If a friend brought this to me, I’d say, ‘I see a lot of red flags,’ ” she said. Willingham has come up with a ten-point list for distinguishing real science from pseudoscience, and the FGP’s website met several of her criteria for the latter. There are extraordinary claims with scant evidence to back them up; invitations to join an exclusive club; the use of “science-y” language that sounds impressive but doesn’t mean much. “ ‘The neurosomatics of ultimate performance,’ ” she said, referring to one of Wheal’s self-proclaimed areas of expertise. “That is very science-y.”

The hype extended to Stealing Fire’spromotional campaigns. In their bios, on their LinkedIn pages, and in press materials, both Wheal and Kotler have described the book as a Pulitzer Prize nominee, but this is a misleading claim. Anyone can nominate a book for the Pulitzer Prize merely by filling out an application and paying the $75 entry fee. The prize administrators recognize only finalists and winners and explicitly “discourage someone saying he or she was ‘nominated’ for a Pulitzer simply because an entry was sent to us.” Wheal says the publisher nominated the book for the prize and that making a big deal of the nomination was Kotler’s doing. (Kotler didn’t respond to requests for comment on that allegation.)

For some of Wheal’s detractors, his work with Goldman Sachs, Deloitte, and Nike exemplified a worrying trend in what you could call the New New Age: radical ideas getting warped into a shape that’s palatable to the powerful and thus drained of their transformative power. Think corporate wellness programs, Big Pharma psychedelic therapy, and the narrow, navel-gazing religion of personal optimization. When I asked Matthew Remski, a cohost of the Conspirituality podcast, about Wheal, he sighed. “He’s going to be really useful for wealthy tech bros who want to make their Burning Man fantasies about global improvement through personal development look really smart.”

Wheal lecturing at a Flow Genome Project retreat near Eden, Utah, in 2017.Michael Friberg/The New York Times/Redux

When we spoke, Wheal seemed to want to distance himself from much of his corporate work. I mentioned that Stealing Fire was categorized as a business book, and he laughed incredulously, as if the idea were ludicrous. When I asked about parts of the book that couched psychedelics as corporate performance improvers, he shook his head. “Well, I only wrote fifty percent of that book,” he said. (He and Kotler no longer work together, and despite his aversion to the term “flow,” Wheal has kept control of the Flow Genome Project. Kotler now runs a rival flow-themed consulting company, the Flow Research Collective, and is based in Lake Tahoe. Neither would discuss their falling-out. “I want nothing to do with Jamie,” Kotler wrote in an email.) When I asked Wheal about his work with Goldman Sachs, which is prominently featured on his company’s website and in his bio, he told me that he’d been hired to speak there only once, on “some bullshit flow-hacking blah blah blah.” He said that he “tore up the talk on peak performance and flow states and basically ripped them a new one” by denouncing the company’s role in destructive late-stage capitalism. He says he has not been invited back.

This, it seems, is the Wheal paradox: he can articulately critique the perils of scarcity marketing (which fuels consumption by exploiting the fear of missing out) and overhyped lifestyle gurus, although, if you were judging from his online presence, you might mistake him for one of the hucksters he decries. He attributes some of this to marketing miscues: “The commodification of all things bourgeois bohemian has led to a lot of crossed wires optically on how we might present.” The difference, he tells me, is that he’s truly lived the life he’s selling.

Increasingly, plenty of other people are living lives that look, at least superficially, quite similar. Army generals dance at Burning Man; young people drive their camper vans to beautiful, remote places. The whole world, it appears, is seeking out the peak experiences that Wheal has long trumpeted. And what has it gotten us? Mountaintops clogged with attention-seeking Instagrammers, venture capitalists investing in psychedelic start-ups, the wellness world in thrall to influencer culture.

As I heard him say on a podcast recently, “The worst people are doing the best drugs.”

In April, Wheal hosted a Zoom conversation with a dozen panelists—among them experts in Zen meditation, neurohacking, and psychedelics—to celebrate the publication of his second book, Recapture the Rapture: Rethinking God, Sex, and Death in a World That’s Lost Its Mind. Speaking from his home studio on Lake Austin, Wheal said an early reader described his latest project as “What if Aleister Crowley [a British occultist born in 1875] hired Malcolm Gladwell as his ghostwriter?” At one point, his face froze, then vanished. The crowd, accustomed to unusual phenomena, was unfazed. “JAMIE HAS TRANSCENDED THE PHYSICAL REALM AND IS NOW A SPINNING DIGITAL CIRCLE,” someone wrote in the chat.

The book is Wheal’s attempt to reckon with the troubling state of the world. It also seems to be an effort to distance himself from the “peak performance Silicon Valley blabbity blah,” as he puts it. Recapture the Rapture opens with a portrait of a world where faith in institutions has collapsed, leaving people vulnerable to charismatic, cultlike movements, which Wheal sees in everything from the influencer economy and ethno-nationalist political parties to cancel culture. Even going along with Elon Musk’s quest to found a Mars colony seems to Wheal a kind of dangerous escapism, an example of how fleeing our problems is more appealing than digging in and addressing them.

“Jamie has transcended the physical realm and is now a spinning digital circle,” someone wrote in the chat.

The rest of the 320-page book details Wheal’s prescription for dealing with all this. The writing can be unwieldy—it’s the first book he wrote without Kotler, and you can feel his Wilber-ish urge to fit everything in there—but Wheal’s ultimate message seems to be that we each need to find “rapture” (that is, inspiration, connection, healing) not via gurus or escapism or designer drugs but through readily available means: breath, sex, music, community. There’s little in Recapture the Rapture about politics or large-scale social change; instead, the revolution that Wheal urges is largely internal, or occasionally communal.

It’s also a book that seems at war with itself. At moments, it reads as though Wheal, or his publisher, is trying to pretend this is another airport best-seller. There is a “Vital Respiration Protocol” and a “Meaning 3.0 Flywheel,” which is “kind of like the blockchain of conscious culture.” Buzzwords are strewn about. But every time Wheal begins to deliver an actionable idea, the book spins off into something stranger and harder to follow. Recapture the Rapture culminates in a final section that Wheal described to me, somewhat impenetrably, as “a rational mystic’s protocol for self-initiating into twice-born humans that can sacrifice their lives with courage on behalf of love to save future generations.” For better or worse, it’s hard to imagine it distilled into a snappy TED Talk; its sales have been predictably underwhelming. “It’s a batshit book to have written,” Wheal admitted to me.

As we left Barton Creek and headed back up the Hill of Life, some of the urgent patter seemed to drain out of Wheal. We walked back to his van, Aslan trotting ahead of us, and he told me that he’d made peace with the idea that Recapture the Rapture might not find an audience, at least in the short term. “Everyone thinks, ‘Oh, I want a life of purpose, I want to find my special purpose.’ And it’s like, ‘Be careful,’ ” he said. He seemed weary, or perhaps just tired of explaining himself to me. “If I am crushed by the grief of the world and don’t know how to get up today, then what on earth am I doing, presuming to say this is a way forward? All I can say is, this is my best crack.”

Rachel Monroe is the author of Savage Appetites: True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsession. She lives in Marfa.

This article originally appeared in the October 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Reluctant Guru.” Subscribe today.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://yogameditationdaily.com/meditation-retreats/refined-plans-for-a-modern-buddhist-temple-are-to-be-approved